The Little League World Series, which runs from Aug. 17-Aug. 28 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, celebrates its 75th anniversary this year as the crowning event for an organization that has prohibited racial discrimination since its founding.

Black boys were playing in Little League years before Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball in 1947 or the U.S. Supreme Court declared school segregation in public schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

But in 1955, Little League Baseball found itself in a civil war when white teams in South Carolina, Florida, and Texas refused to take the field against Black teams as part of a massive resistance to the Brown decision. Southern politicians feared that if Little League tournaments and other sports were integrated, so, too, would schools, swimming pools, movie theaters, and lunch counters.

“The South stands at Armageddon. The battle is joined. We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in this dark and lamentable hour of struggle,” Georgia Gov. Marvin Griffin said. “There is no more difference in compromising the integrity of race on the playing field than in doing so in the classroom. One break in the dike and the relentless seas will rush in and destroy us.”

In South Carolina, white teams withdrew from district and state tournaments rather than share a ballfield with the Cannon Street YMCA all-stars, a Black team from Charleston. The Cannon Street team won those tournaments by forfeit but was declared ineligible for the regional tournament because Little League Baseball’s rules said a team could only advance to that level by winning on the field.

In Florida, a Black team, the Pensacola Jaycees, advanced to the state tournament after white teams refused to play them. A white team from Orlando agreed to play the Pensacola team in the state tournament. The Orlando team won.

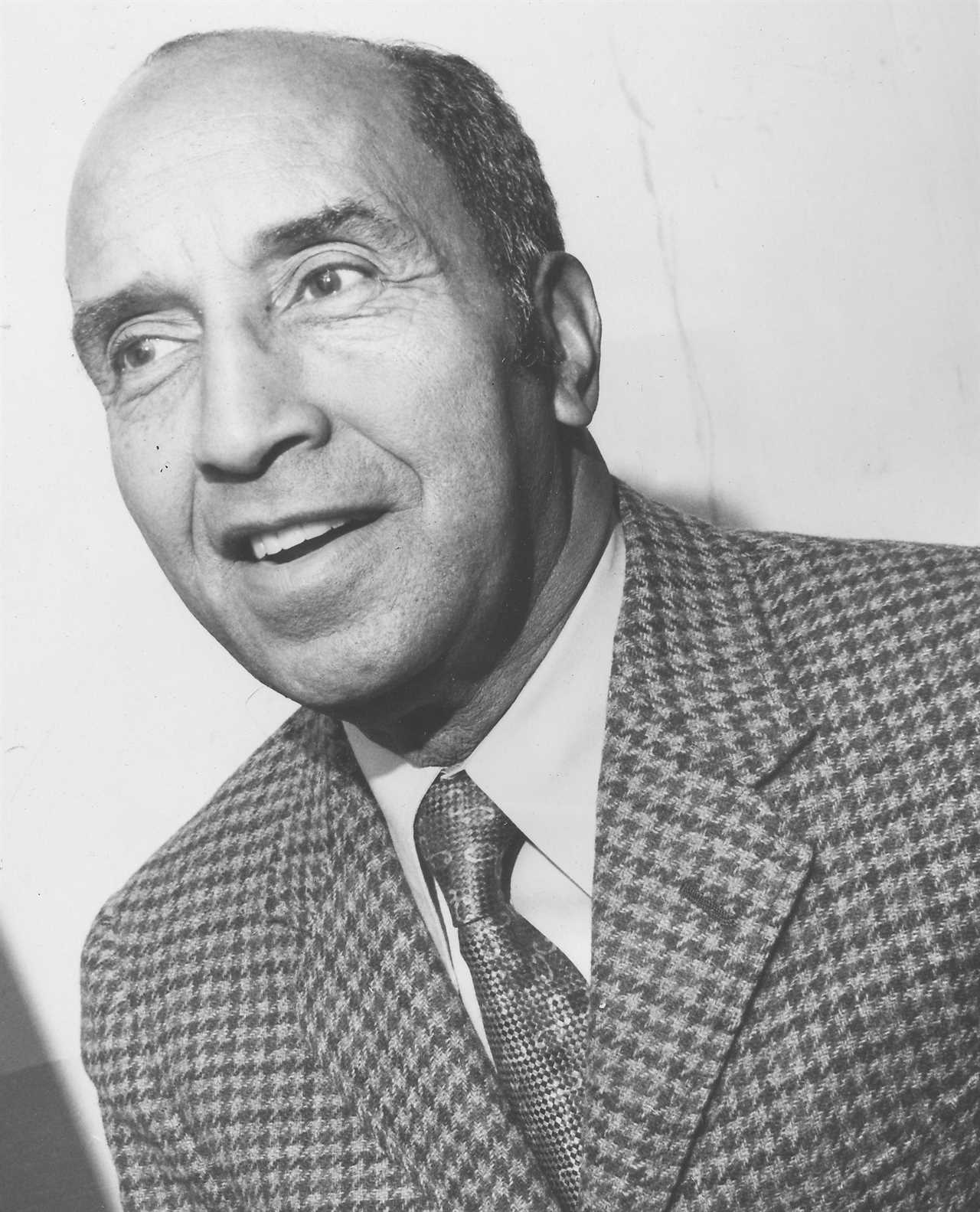

Sam Lacy, the sports editor of the Baltimore Afro-American who had lobbied for the integration of Major League Baseball, wrote that the fact the game was played was more meaningful than who won. The Pensacola team lost on the field, he said, but won “on the scoreboard of human relations.”

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

He compared what happened in Florida to what happened in South Carolina. “After it was pointed out that the admittance of the colored boys was entirely legal, the South Carolinians declared they’d have none of it,” Lacy said.

If things were left to children, Lacy said, there would be no color line. He said he believed that “the South’s hostility toward integration is kept alive solely by adult leaders.”

Lacy decided to test that idea in Williamsport that year. He drove 200 miles to the Little League World Series to ask white 11- and 12-year-old ballplayers and their fathers whether white boys should share the same baseball field with Black boys.

Among the adults he interviewed was Sam Despine Sr., who managed the Alexandria, Louisiana, team, where his son Sam Jr., was the star pitcher. The Alexandria team had defeated a Black team from Texas in the regional tournament. The father said his team played the game because Little League’s rule said it had to. Sam Jr. said it made no difference to him whether he played against Black or white boys.

Lacy also interviewed Robert Salter of Auburn, Alabama, whose two sons were scheduled to play an integrated team from Delaware Township, New Jersey.

Salter said he didn’t want his sons playing against a team with Black players. Integration, he added, would happen when the country was ready for it. “We don’t like the idea of being told we’ve got to do something,” he said.

Lacy asked Salter if Black people had not been waiting for white people to grant them equal rights for a century.

Salter ignored the question, Lacy said.

“You know, there are people in your race,” Salter said, “that you don’t want anything to do with yourself. Well, we feel that way in the South.”

Lacy said that every group has people like that.

“You’re right about that,” Salter said. “But in the South we don’t have many of that kind in our race and they predominate among the colored people.”

Lacy then asked Salter if Black boys should be allowed to play with white boys in Little League Baseball.

“Let ’em play among themselves. That’s the way it should be. Sure, there’s a lot of agitation about this thing, but that doesn’t help matters any,” Salter said. “It just serves to make things worse.”

Lacy then asked Salter’s sons, identical twins George and Frank, what they thought about playing against Black boys.

“It didn’t make any difference to me,” one of them told Lacy (who admitted he could not tell the brothers apart).

“To me, either,” the other said.

Lacy, who was then 51, had grown up in Washington attending games with his father at Griffith Stadium. Lacy watched white major league teams play on some days and Black teams on others. He said he saw many Black players who were good enough to play in the majors but were denied their opportunity because of the color line.

As a sportswriter, he fought for the inclusion of Blacks in the majors for a decade before the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson. Lacy would later receive the BBWAA Career Excellence Award from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America for his contributions to racial equality.

Segregation kept him from working for mainstream newspapers and from having a press card that would have allowed him in press boxes, clubhouses, and dugouts. But working for the Afro-American allowed him to criticize bigotry and racism.

Lacy would not have been able to do that if he had worked for most white-owned newspapers, where journalists, even in the North, rarely addressed racism for fear of alienating readers and advertisers.

That is, until the horrific slaying of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, on Aug. 28, 1955, shortly after the conclusion of the Little League World Series.

Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff wrote in their Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, that the September 1955 trial of the men charged in Till’s slaying brought an unprecedented number of Northern reporters into the Mississippi courtroom. Their readers were horrified by the details of Till’s lynching and the exoneration of the men who later admitted to killing the boy.

Lacy’s Little League column appeared in the Afro-American on Aug. 30, two days after Till was killed and a day before his body was found.

-----------------------

By: Chris Lamb

Title: When integration was front and center at the Little League World Series White teams from the South were refusing to take the field against teams with Black players as a protest against ruling in Brown v. Board of Education

Sourced From: andscape.com/features/when-integration-was-front-and-center-at-the-little-league-world-series/

Published Date: Wed, 17 Aug 2022 14:08:30 +0000