Excerpted from Stolen Dreams: The 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars and Little League Baseball’s Civil War.

The Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars did not know when they left Charleston, South Carolina, on August 24, 1955, to go to the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, that they were riding into something that was ripping the country apart and confronting how Americans saw themselves and each other. It would not be clear to those 11- and 12-year-old African American boys for years, perhaps decades, that they were part of the struggle for civil rights in the United States.

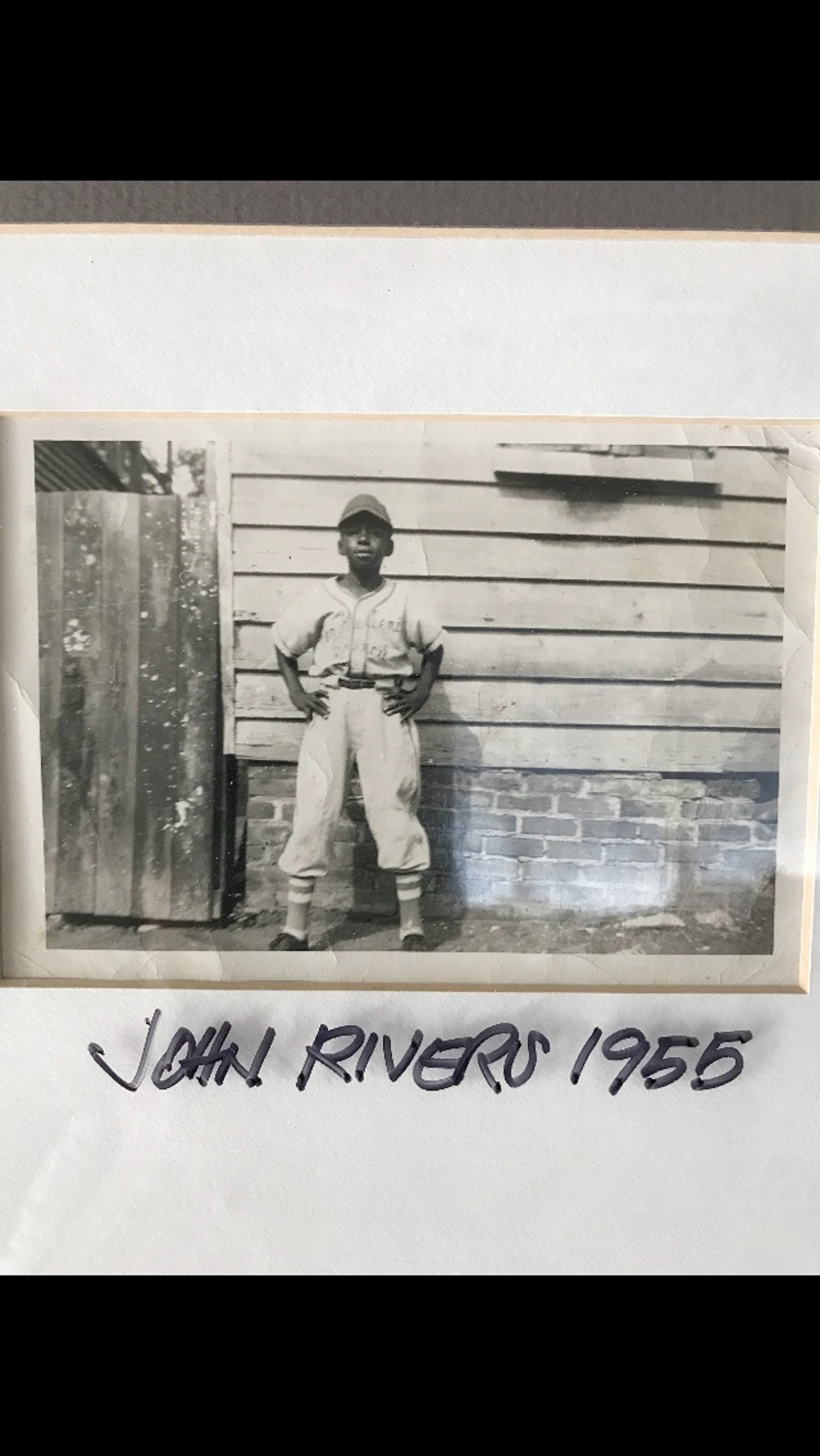

John Rivers, the team’s shortstop who became a successful architect, was asked when he was in his seventies to describe the team’s significance. “It’s part of American history. It’s part of the civil rights movement,” he said. “If you strip away baseball, it’s part of the 1950s movement. It’s tied to Brown v. Board of Education.”

This is the story of an African American Little League Baseball team that entered a baseball tournament in the summer of 1955 and all hell broke loose. White Little League teams refused to play the Black team and the boys on that team were denied their dream of playing for a chance of going to the Little League World Series. It is the story of how racial discrimination “scarred the souls of Black children,” as historian Lee Drago put it. “How much harm did it do to the little kids’ souls. It caused them to doubt their self-worth, to diminish their pride. They took on a bad image of themselves. It got in their soul.” John Rivers said the pain of that summer never went away. “You carry it with you your whole life,” he said. “Some people overcome it. As I get older, I think about this more. You can achieve a lot. But you’re still scarred for the rest of your life.”

The former All-Stars spent much of their lives trying to forget what happened to them that summer and the rest of their lives telling people why their story must be remembered. William “Buck” Godfrey, a member of the team, called his memoir about the Cannon Street All-Stars “The Team Nobody Would Play.” Creighton Hale, who was once chief executive officer of Little League Baseball, described the Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars as “the most significant amateur team in baseball history.” Gus Holt, who revived the story long after it had been forgotten, said the story of the team is a twist on an old story. “Man’s inhumanity to man has been a constant through history,” Holt said. “This is about man’s inhumanity to kids.”

White supremacy runs through the history of Charleston. But so, too, does Black resistance. There were slave rebellions and race riots in Charleston. African Americans confronted racial discrimination during and after World War I and World War II and during the civil rights movement, and they continue to do so today in response to unrelenting bigotry and unspeakable tragedies such as the murder of nine African American parishioners at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015.

John Rivers

The story of the Cannon Street All-Stars is inextricably linked to postwar Charleston and a white federal judge, J. Waties Waring, who broke with his aristocratic family and decided in one ruling after another that racial discrimination was unconstitutional. Waring’s nephew, Thomas, the editor of the Charleston News and Courier, became the voice of segregation and white supremacy.

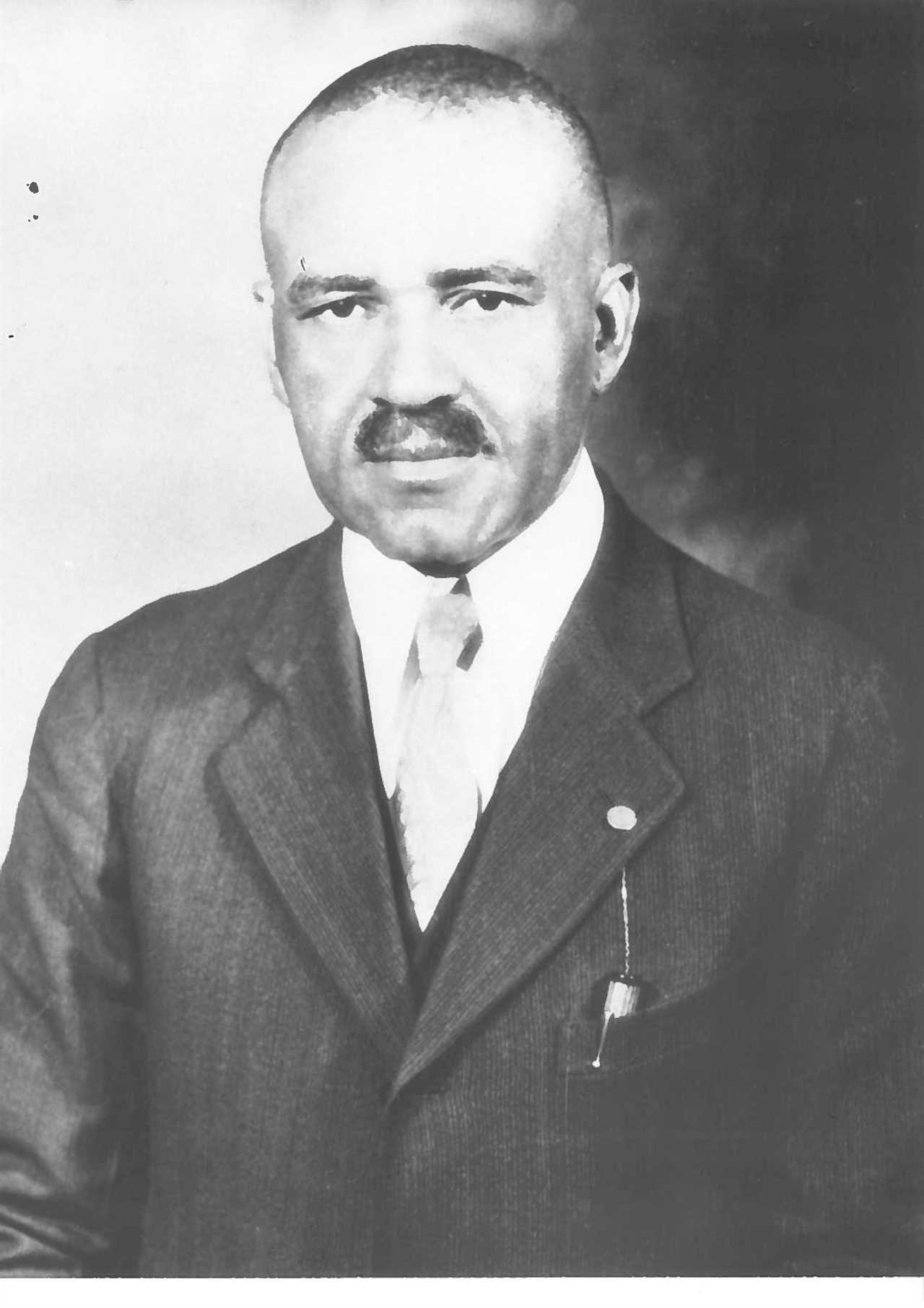

Danny Jones, the director of the parks and recreation department and the state’s director of Little League Baseball, found himself torn between the rules of Little League Baseball that prohibited racial discrimination and the laws and customs of South Carolina that prohibited integration, but then sided with the segregationists. Jones’ primary antagonist was Robert Morrison, an African American businessman, who had been a racial accommodationist most of his life; but in the last decades of his life he became a race man.

Morrison, the president of the Cannon Street YMCA in downtown Charleston, was in his seventies when Little League Baseball approved his application for a league. His tired eyes saw beyond the white lines of a baseball field. He knew there were no Black teams in any of the Little Leagues in Charleston or anywhere else in the state. If youth baseball could be integrated in Charleston, he thought, so could municipal parks, swimming pools, and schools. If there could be equal opportunities for Black kids, there could be equal opportunities for Black adults. He intended to use the Cannon Street team and Little League Baseball to further that agenda.

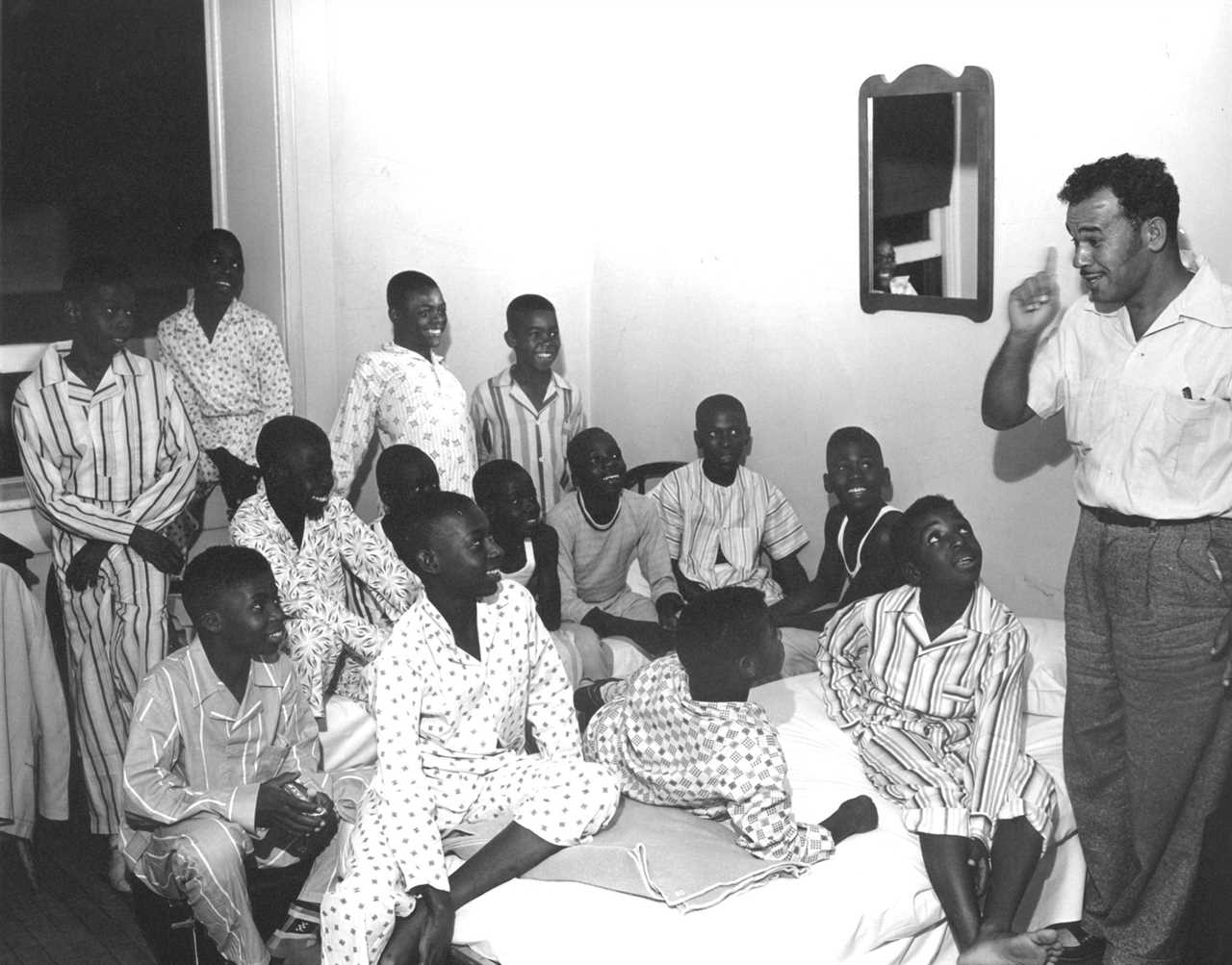

The news of a league for Black boys meant one thing to Morrison but something else to the 9-, 10-, 11-, and 12-year-olds who lived on the peninsula, some of whom had been playing baseball with broomsticks and rubber balls that were cut in half. To those boys, it meant wearing uniforms and playing with bats and baseballs on a diamond with bases and chalked basepaths and an outfield fence for home runs and having your family cheer you from the bleachers.

During the early spring of 1954, dozens of boys tried out for one of the league’s four teams. When the season ended, the best players from every Little League team were selected for an All-Star team that played against other All-Star teams in district tournaments throughout the state. The winner of the tournament advanced to the state tournament. If you won that tournament, you went to one of eight regional tournaments. If you won one of the regionals, you played in the Little League World Series in Williamsport. The Cannon Street YMCA league did not have a team in that year’s Charleston tournament because first-year leagues were not eligible.

When Morrison registered the Cannon Street All-Stars for the district tournament the following summer, it put Morrison, the All-Stars, and the forces of integration on a collision course with Danny Jones, Thomas Waring, U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond, and the state’s political establishment. The Brown decision prompted Waring and Thurmond to call for massive resistance against any attempt to end segregation. “Segregationists believed that any crack in white solidarity constituted an existential threat to white supremacy,” Richard Gergel, a federal judge in Charleston, said.

Jones did not object when Morrison told him he wanted to start a Black Little League because he probably thought its players would stay on their own diamonds and white players would stay on theirs. Jones supported baseball for African American children, but he drew the line at Blacks and whites playing on the same field.

All the white teams withdrew from the district tournament. The Cannon Street team won by forfeit and advanced to the state tournament. Jones, who was responsible for organizing the state tournament, petitioned Little League Baseball’s president, Peter McGovern, to have a segregated state tournament. McGovern rejected the request because it violated the organization’s rules prohibiting racial discrimination. Jones then resigned as state director of Little League Baseball. All the white teams withdrew from the state tournament, leaving only the Cannon Street YMCA team.

Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, College of Charleston

Having won the state tournament by forfeit, the Cannon Street team advanced — or at least should have advanced — to the regional tournament in Rome, Georgia. If they won there, they would have played in the Little League World Series. This did not happen. Rome’s director disqualified the Cannon Street team because it had advanced by forfeit. Little League Baseball’s rules said that a team had to play and win at least one game in each qualifying tournament. Morrison appealed the decision. In his response, McGovern expressed his regret for excluding the Cannon Street team but maintained that the organization had to follow its own rules.

This was the end of the team’s season and the end of their dream of playing in the Little League World Series, and, although nobody knew it at the time, the end of Little League Baseball in South Carolina and in much of the South. Jones created the Little Boys League and the league’s charter excluded Blacks. The Little Boys eventually changed their name to Dixie Youth Baseball, which is still being played throughout the South.

Thomas Waring defended Jones’ decision to resign from Little League Baseball and the white teams for refusing to play the Cannon Street All-Stars. He said it was not their fault that the tournament had been canceled. It was the fault of northern agitators. “The Northern do-gooders who have needled the Southern race agitators into action may have to answer for their consequences,” Waring wrote. The editorial did not identify the “Northern do-gooders.” It did not have to. Waring’s readers knew, because he was regularly criticizing the communists and agitators in the North, including the U.S. Supreme Court, who interfered with the rights of southerners to live as they chose.

The Supreme Court issued its decision in Brown v. Board of Education shortly after the Cannon Street Y Little League began its first season. In its unanimous ruling, the court cited the impact that segregation had on children. “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children,” the court said. “The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group.”

A year later, on May 31, 1955, the court returned to Brown, in what became known as Brown II, restating the “fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional” and “all provisions of federal, state or local law requiring or permitting such discrimination must yield to this principle.” Thurmond expressed his contempt for the Supreme Court in speech after speech in the U.S. Senate. He called for southern states “to resist integration by any lawful means.”

Little League Baseball and Softball

Little League’s McGovern could have made an exception to the organization’s rules and allowed the Cannon Street team to play in Rome. But he did not. This deprived the boys of the dream of going to Williamsport. The boys were left with a question that has haunted them the rest of their lives. What if they had played in Rome? “We will never know how far we could’ve gone,” John Bailey, one of the Cannon Street All-Stars, said.

McGovern knew that Little League Baseball had played a part, however unwillingly, in this injustice. He invited the team to be guests of Little League Baseball at the World Series in Williamsport. Morrison borrowed a bus from Esau Jenkins, a Charleston civil rights activist who had used it to drive African Americans to register to vote — an act so brazen that it could get a person killed. Morrison’s act of taking a busload of ballplayers and coaches through the rural South to Williamsport was brazen enough. Ku Klux Klan membership had been on the increase since the Brown decision and with it came a rise in the anxiety of southern African Americans. Fifteen hundred Klansmen and their families attended a speech by E. L. Edwards of Atlanta, the KKK’s imperial wizard, in a pasture outside Conway, South Carolina, a hundred miles north of Charleston.

The adults decided to leave at nightfall and drive north through the night to avoid raising suspicion. Many of the boys’ parents were worried about the dangers involved in sending their sons hundreds of miles — most of them on country roads that ran through rural towns, where the boys and their coaches would not be allowed to eat in restaurants or use public bathrooms.

The bus broke down outside of Williamsport and the team was towed into town. After breakfast with the other All-Stars the next morning, they went to the stadium to watch the championship game between Morrisville, Pennsylvania, and Delaware Township, New Jersey. The Cannon Street players and coaches were each introduced to the standing-room-only crowd. There was heartfelt applause from the crowd — many of whom had read about the team in newspaper articles. After all the players and coaches were introduced, the Cannon Street players remembered, there was more applause, and then came a voice from the bleachers.

“Let them play!” it said.

Someone else repeated the words. Others began chanting the words. The words became louder and louder. “Let them play!”

“Let them play!”

The response gave the Cannon Street team chills. The players on the team have repeated those words over and over. They say they can still hear them several decades later.

“I remember it as if it were this morning,” Rivers said.

The Cannon Street team and coaches watched the game from their seats. What is it like to get so close to your dream and see someone else living it? “It remains one of baseball’s cruelest moments,” Boston Globe columnist Stan Grossfeld wrote in 2002.

The team got back on Esau Jenkins’ repaired school bus on the morning of Sunday, August 28, several hours after Emmett Till, not much older than the Cannon Street players, was snatched from his uncle’s house in Money, Mississippi, and was tortured, murdered, and dumped into the Tallahatchie River. On December 1, a little more than three months after the Cannon Street boys went to Williamsport on a bus, Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery, Alabama, for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a municipal bus. This began a year-long boycott of Montgomery buses. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional.

The stories of Emmett Till, Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery bus boycott remain defining events of the civil rights movement. The Cannon Street All-Stars team was a national story for a few weeks and then it disappeared. But the All-Stars never forgot. It remained a source of pain and rejection and sorrow.

This story would have remained buried if it were not for Augustus Holt, who unearthed the story decades after it happened. In 1993, Holt’s son Lawrence made the All-Star team in the Dixie Youth Baseball League, which had long since been integrated. When Lawrence put on his uniform, his father glared at the patch of the Confederate flag on the sleeve. Gus’ anger turned to curiosity. He investigated how the Confederate flag — the symbol of white supremacy — had ended up on his son’s uniform. He learned about the Cannon Street All-Stars and how the Dixie Leagues had been created.

Holt began contacting the former All-Stars, who were then in their fifties. He organized a reunion. He brought Little League Baseball back to Charleston. In 2002, the Cannon Street All-Stars returned to Williamsport to the field where they had not been allowed to play and the disappointment of the day long ago washed over them with their tears. They were finally awarded the state title they had won in 1955. There would be stories about them in newspapers and on radio and on television. “There’s no sex or violence or murders,” John Bailey said. “But [ours] is a great story.”

-----------------------

By: Chris Lamb

Title: When a Black team entered Charleston’s Little League tournament in 1955, all hell broke loose The boys lost their chance to play in the World Series because white teams refused to face them

Sourced From: andscape.com/features/when-a-black-team-entered-charlestons-little-league-tournament-in-1955-all-hell-broke-loose/

Published Date: Fri, 01 Apr 2022 12:21:24 +0000